Hi, this is Eliot, a fellow in the Fellowship cohort of 2019-2020 for Open Lunar. In December 2019 we held an event on the Norms of Behavior in Space, in partnership with the Secure World Foundation. We had a focused and in depth exploration of frameworks and tools for guiding how space organizations can use the concept of norms to support pioneering activities in the burgeoning space economy and community. We also covered public choice theory and how it applies to the lunar context. This is the first of a two part series developed from the event.

Part 1: Norms

Norms are an approach to inter-agent regulation that can be used in many contexts. Whether you’re a space enthusiast or want to port our lessons to another industry, we crafted this blog to support folks who could not join our discussion to learn from the ideas we explored there. Much of the contents of this blog has been drawn from the work of Chris Johnson from Secure World Foundation and the introductory content he prepared for the workshop “Emerging Governance Challenges” in December.

What are “Norms”?

Norms are agreements between self-determined actors which start as voluntary but over time they become “standard practice”. States and other organizations constitute many actors in the space industry, and lean on norms to negotiate and represent their interests and balance incentives. Norms are often built around shared values, or long-term communal interests, such as an understanding of the worth of a common good or benefit. This may require a conception of shared interests of actors, but can serve as a normative basis for substantive measures to cooperate when solving problems.

Here’s an example of a Norm:

Subsidiarity, or the norm that governance should be run at the most local level to its relevant implementation with direct stakeholders negotiating decisions, is one such norm that we could build around. Considering that governance can be thought to usually work best when specific to the situation, and no two situations are exactly the same, the introduction of this actor-level decision specificity to policies could add relevance, clarify stakeholders, and allow flexibility for different regimes in different specific contexts.

What are Norms good for?

Many early lunar efforts hinge on resource utilization and coordination. In order to plan for how these will be managed we can look to modern and historical analogs as policy frameworks and sources of insight. We can learn from modern resource management and public choice theories as they’re used on Earth to think about the necessary incentives for a space-based regime. Creating norms and reacting to them can be thought of as prototyping activities for future policies, which allow coordination problems to surface and be resolved before a policy is official.

Part 2: Public Choice Theory

The other main topic we reviewed during the meeting behind this article was Public Choice Theory - and how this might inspire normative behaviors or be considered as a framework for space policy precedent setting. This content, is derivative of that largely developed and presented by Jessy Kate Schingler.

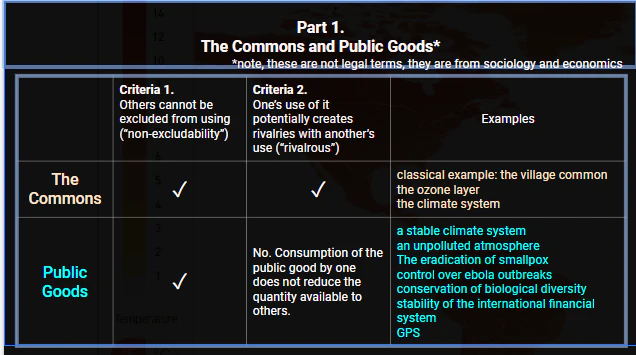

The Commons and Public Goods

One set of concerns where coordination problems between actors have been deeply explored are those that occur when actors have a shared resource they all benefit from.

By the Commons, we’re referencing things that everybody benefits from, like Earth’s free oxygen. Telling others that they can’t have it isn’t an option, and their breathing isn’t harming or hindering you.

By Public Goods, we mean things that give mutual benefit, but require an investment or labor or self-restraint to keep beneficial, like a water system that’s clean and healthy, or GPS systems. Benefitting from Public Goods doesn’t make them less good for others. An important distinction here, between commons and goods, is that with public goods, there’s a metric of rivalrousness; where bad stewardship could hinder someone else’s free use of a mutual benefit.

Are there subcategories here?

Certainly. Public goods have to be started and/or maintained in different ways. Some ways for providing public goods are additive, like distributing free wifi routers or solar technology. Some are more like best-shot technologies where it only matters what’s best, like cures for diseases. Alternatively, some public goods like infection containment are maintained only through the strength of their weakest link.

What fosters public goods?

The following concepts are some of the known tools that foster public goods, but they are not all-encompassing notions.

With Privatization there is the option of State control or monopoly-allowance of a good, such as when a State allows for public-land purchases. Whoever owns a thing usually takes care of it, and States have sovereignty within their territories to give things in this manner. This approach tends to maximize use-rights and owner benefits, but it doesn’t spur action on inter-actor obligations or long-term, broader benefits. We judge that this may be useful, but isn’t sufficient for dealing with global anthropogenic problems, or for extraterritorial management.

With Regulation, we can lean on international agreements or similar hard law, soft law, and voluntary commitments that can be signed. This is necessary, but not sufficient, because often the actors are too numerous, the changes too rapid, and the administrative costs too high. Regulations also allow for problems like a dependency on weakest-link technologies, and the possibility of workarounds. Some solutions exist. For example, creating trade restrictions against havens where free riders escape duties, or agreement funds for assisting actors with compliance. Effective regulation tends to need high-quality monitoring, actor review of the monitoring, transparency of monitoring data, and compliance systems.

With Incentivization, Economic and Market Forces can be brought into the equation. Fees or quantitative limits can be attached to activities, for example. This brings low administrative costs if well designed, but the arrangement of this brings its own set of open-ended questions. What is the order of preference allocation? How affordable is it? Are prices graded along a metric? Are there discounts for old or new users? Like regulation and privatization, we judge this to be insufficient on its own. As with agreements, monitoring and verification is required, and it is difficult to know what limits are sustainable prior to pushing them.

With Cooperation voluntary measures and actions take place for mutual realization of long-term interests, moral or values-based responsibility, or building reputational value. This can be induced by positive-sum games producing public goods and realizing clear net-positives for all. A clear example of this is weather data. This can similarly be accomplished via decreasing-sum games that avoid mutual harms. This usually requires information about the options available, benefits and costs, and the behavior of other actors at hand, which in turn requires monitoring, transparency, and measures to ensure compliance. Norms are very important here in particular, but also affect each of the other mechanisms.

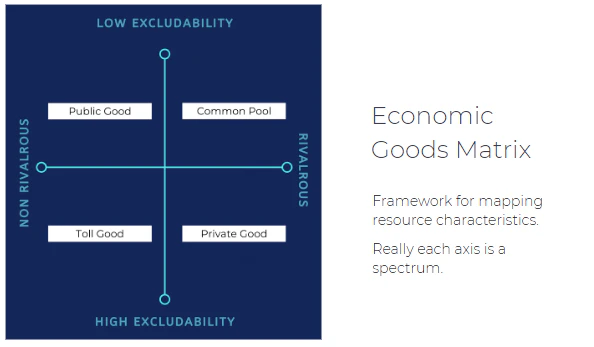

Adding depth to this model - The Economic Goods Matrix

Some things that everyone benefits from are Excludable, or the use by some can be controlled by others. For example, building a park, museum, or zoo brings a potential public good to all locals, but only as far as the builder does not add a toll booth or other cost-recouping mechanism. Toll Goods are not rivalrous (use does not interfere with another's' use) but are excludable (a gatekeeper can say “no” to accessing it). Similarly, rivalrous (your use might interfere with mine - full garage) and excludable (I can tell you “no entry”) goods, like parking garages, are categorized as Private goods.

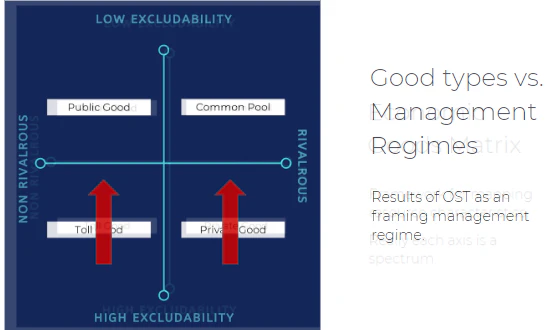

The Outer Space Treaty and the Commons

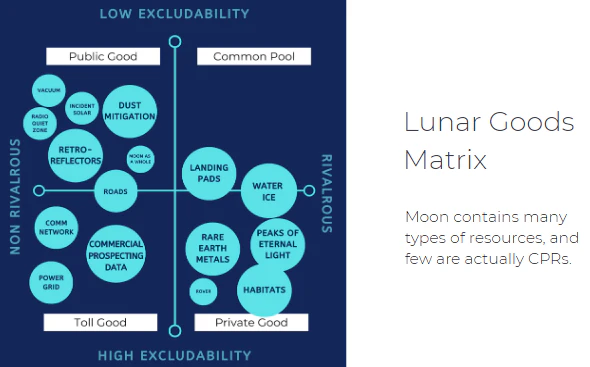

We often refer to Space as a Commons, because Article 1 and 2 of OST refers to some key shared agreements about Management rights. This agreement, including things like “nobody owning the Moon”, means that excluding others from excludable goods is, in many cases, not an option, eliminating those bottom two sections of the chart above. See below for what we figure that means on the Moon:

But this doesn’t tell us what, specifically, to do or how to manage it. So, you can consider with the various goods out there in the world, that they come with Bundles of Rights, similar to the rights you’d have over any plot of land on Earth and its resources: There’s the Constitutional Choice Rights, over who gets to have a say about a resource; Collective Choice Rights, over who gets to participate in it; Operational Rights, over who gets to use what, and how; Access, or the right to enter a defined physical space; Withdrawal, or the right to obtain an amount of a resource; Management, or the right to regulate internal use patterns of, and transform or improve the resource; Exclusion, or the right to determine who can have Access, and how that right may be transferred; and Alienation, or the right to sell or lease Management and/or Exclusion rights. These bundles of rights are important factors that must be eventually addressed in any particular solutions, and should be at least considered in proposals to address concerns.

Developing Norms

We’ve discussed public goods and common-pool goods, and why we shouldn’t treat what could normally be private goods as such, so now let's return to the beginning of this article, with Norms. Again, this is not used here to mean ‘normal’, but instead something that has been adopted as a standard practice. There is, importantly, a degree of “Oughtness” in building and following a norm, including social consequences for “Non-Observance”, as non-defectors stigmatize it.

Life cycle of a norm

1. Emergence: Norm “entrepreneurs” call attention to a problem, try to change a behavior, establish some basic, first-iteration standards, and they call these ‘best practices’ that everyone should adopt

2. Cascading: The norms become broadly accepted, and a critical mass of actors accepts the norm, past an adoption tipping point, as it goes from ‘best’ practice to ‘common’ practice. Legal instruments might be needed to get here, but major actors should be in on it.

3. Internalization: The norm is taken for granted, it’s just an expectation now, and is routinely followed even without policing

Norms also eventually die out, through competing norms overtaking it, or forces that encourage the norm becoming weaker than the disincentives. A major challenge for any norm is that it may become easier to flout and destroy norms rather than adhere to them, and actors could make competing norms that work for them, but are counter to established norms, laws, or community interests. For norms that encourage practices that turned out to be unhelpful, this can be a good thing.

Takeaways

This is a bag full of tools for your conceptual toolbox and again, we hope you use them for good. The frameworks above are lenses through which you can analyze potential structural incentives among actors.

Goods Matrixes, Rights Bundles, and principles like Subsidiarity can help frame our norm design thinking. Norms can allow Prototyping of these values and their implementations, which enables building learning loops, strong institutions - and good policymaking.

In the near future, Open Lunar will be publishing a more detailed piece on why now is the time to be developing cohesive, sensible norms for space policy in particular. Developing norms for the space economy can incentivize and accelerate action, provide concrete examples to inform policymakers into the future, enable exploration of precedents and intentionality, and create knowledge for use on Earth.

This has been Eliot from Open Lunar. If you have more topics you’d like to hear from us about, feel free to contact us.